Spencer Bispham/Managing Editor

The first time I came home with a Supreme t-shirt, my family was just as horrified as I was proud. They couldn’t get past the fact that I had spent $70 on a pre-owned, ratty piece of fabric, no matter how much clout its tiny logo gave me at school. I was slightly offended by their reaction at the time, but looking back, they were unknowingly trying to save me from a brand that continues to be incredibly problematic.

For those who don’t know, Supreme is a cult-skateboard clothing brand founded in 1992 by James Jebbia. In the decades that followed, their provocative designs became fixtures of street fashion culture, particularly the iconic red “box-logo.” They’ve sold everything from t-shirts and hoodies to pinball machines, using a weekly drop system to release products during the spring and fall seasons. The releases regularly sell out, because of Supreme’s reliance on artificial scarcity: producing a limited amount of sought-after product to increase the demand. Not only does this prevent consumers from authentically buying/wearing the pieces, but it encourages those who wish to resell them for exorbitant prices on the aftermarket.

Photo courtesy of @fbgsupreme/Instagram

Of course, one could certainly argue that this strategy is just “good marketing,” but in reality it is more complicated than that. The truth about Supreme is that it exemplifies so much of what’s wrong with fashion, specifically when it comes to the role of corporations in the industry.

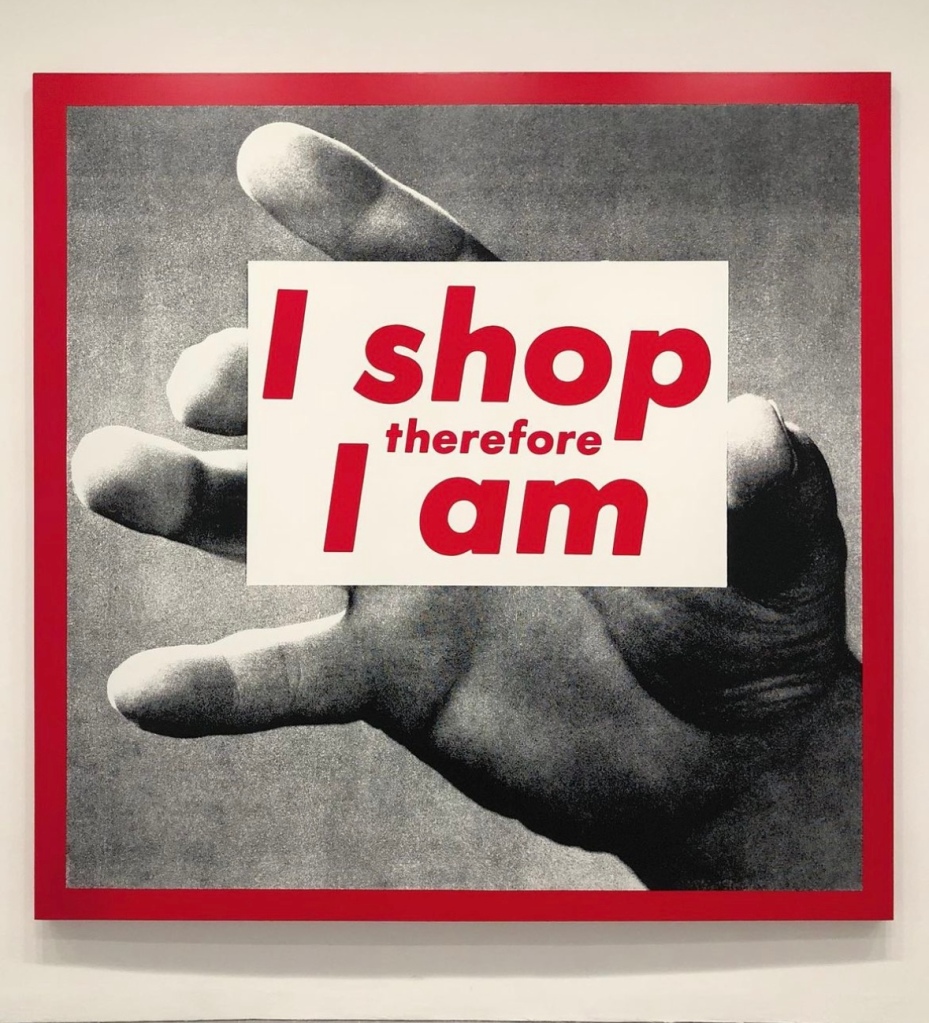

Supreme has been called out a number of times over the years, many times for the intellectual theft of others’ designs. Some of their products have been ripped from smaller designers or marginalized cultural groups, such as the concept for their collaboration with The North Face in 2016, when rapper A$AP Nast claimed they copied his idea. Another example is the Obama anorak jacket from their SS17 collection, which used an iconic textile pattern unique to Ghana. Other complaints date all the way back to the creation of Supreme’s logo, which (very ironically) likely copied the work of conceptual and anti-consumerist artist, Barbara Kruger.

In line with this consistent controversy, the most recent person to check Supreme is the brand’s former creative director, Tremaine Emory. His time there lasted from Feb. 2022 until late August of this year, where he oversaw the production of three collections. Seemingly out of nowhere, Emory stepped down from this position because of what he alleged to be the effects of systemic racism.

Photo courtesy of @lets_talk_about_art/Instagram

Hours after the news of his resignation broke, Emory took to Instagram to vent about his frustration with Supreme. He specifically cited concerns with the company’s lack of diversity

“l left supreme because of systemic racial issues the company has from the treatment of the arthur jafa collab to the makeup of the design studio which has less than 10% minorities working,” Emory wrote in a caption. “the brand is largely based off black culture ask @juliencahn @kyledem and Alex detrich…”

In a later post, he explained that even the founder of Supreme agreed that things may have gone too far with the cancellation of Emory’s collaboration with fellow Black creative, Arthur Jafa

“So the Tuesday after i resigned james jebbia pulled up to my crib… and we talked about why i resigned,” Emory wrote. “James admitted he should have talked to me about cancelling images from the jafa collab…”

Although Emory’s sudden exit speaks to Supreme’s inability to respect and acknowledge those producing their designs, it ultimately falls atop a long list of similar accusations. The brand’s problematic business ethics also drew the attention of comedian Hasan Minhaj, who dedicated an entire episode of his Netflix show “Patriot Act” to illustrate the problems with their business model. In it, he mentioned The Carlyle Group, an investment firm which owned Supreme until 2020, and their ties to the military manufacturers, Wesco and BAE Systems.

“Together, Wesco and BAE support a fighter jet called the Typhoon, which is used by the Saudis to bomb Yemen,” Minhaj said. “This [The Carlyle Group] is a company that profits off of war and obesity. Why are they trying to sell Supreme fanny packs to dudes with man buns?”

The answer is simple: profit maximization. That is the literal goal of any investment firm; to make the largest possible returns on their patrons’ money. None of the biggest names in Western fashion are exempt from corporate meddling either: Gucci, Dior, Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Karl Lagerfeld and others are all under the thumbs of some of the wealthiest people in the world. Unsurprisingly, all of the aforementioned brands have also been called out at some point in time for the misuse of others’ intellectual property and/or cultural appropriation. Gucci specifically has been the subject of complaints about creative control when it came to Tom Ford’s decision to leave their womenswear line in 2004.

All of this information makes Supreme the perfect example of why corporations should not be involved in fashion. Their drive for financial gain primes them to steal and cheat their way to the top, no matter who they might hurt in the process. These terms get even more literal when you look at all of their investments, some of which can be traced down paths of death and destruction. Worst of all, they directly infringe on designers’ ability to foster creativity and self-expression: the true function of fashion as an art form.

Leave a comment